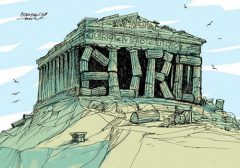

Under the umbrella of the West. The Greek Crisis and the rise of the Leftists

What is happening in Europe?

Is the Euro threatened by the rise of the Leftists in Greece?

Will Greece exit the Eurozone?

How will Greece manage to pay its debts?

Is The European Union on the wane?

This essay attempts to answer all these questions.

The Mosaic of the EU Nations

Europe is not populated by a homogeneous group of people. The word “European” is very broad and vague. The Northern Europeans do not have the same idiosyncrasy and the same way of living with the Southern Europeans.

For example, the Germans feel closer to the Austrians, the Finns, the Dutch and the Danish while the Italians have much more in common with the French, the Greeks and the Spaniards. In other words, the peoples of the Mediterranean Sea have a completely different approach to life from the peoples living in the North of Europe. The North accuses the South of being “lazy” and “counterproductive”. The South blames the North for being “cold blooded” and “insensitive” to the suffering masses.

The Irish and the Scots however, are somewhat closer to the European southerners perhaps because they are of Celtic origin that differentiates them from the Germanic tribes of the North.

On the other hand, the British seem to be completely different from everybody else in the continent. The British do everything possible to distance themselves from the EU and are somewhat willing to abandon it sooner or later. The British accuse the French of being in love with bureaucracy and the French accuse the British of being “professional controversialists and vulgar”.That is long story, however, that goes back in time. When Henry VIII entertained Francois I of France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, the French king, himself patron of Leonardo da Vinci, sneered at Henry’s vulgar English taste. „His idea of grandeur,“ he remarked, „is to put a lot of gold over everything. No class.“ The political and military fissures were reinforced by cultural ones. Voltaire was rather impressed by the English constitution. But on his return to France he told his countrymen: „I imagine a country with 350 religions and only one sauce!“

The French have never forgiven the British for humiliating them at Fashoda in Sudan in 1898, an incident few British remember. A French force had to withdraw from the Nile after a British ultimatum, ending their ambitions for a trans-continental African empire. They still resent the way the British kept Napoleon Bonaparte prisoner in St Helena.

That is obvious due to the Scottish referendum, which almost separated the Scots from the British and shook the foundations of the European Union causing an unprecedented anxiety to the European leaders.

The Gate of Calais,

William Hogarth, 1748,

Tate Britain, London.

Hogarth, the famous English painter was disgusted by the poor quality of French beef. His famous painting, “The Calais Gate”, shows the French as virtually starving.

The French retaliated by deporting him as a spy. France has a lot of carefully nursed grievances against the British.

The French hate Winston Churchill for reluctantly ordering the destruction of their fleet at Oran and Mers el-Kebir in 1940. They also blamed him for the loss of their colonies in Syria and Lebanon.

Most of all, the French hate the British for burning Joan of Arc at the stake. De Gaulle brooded on this ancient injury till his dying day. Nowadays, French resentment centers around the invasion of the French language by English slang. The French have indeed a very a beautiful language and the speed in which franglais, as they call it, is taking over must be heartbreaking and painful.

About one in four nouns used by young French people today is an English import. The Academie Francaise, the official custodian of the language, refused to include these words in its dictionary, the French parliament legislates against them, and the government bans them from official correspondence and state schools. To no avail, however.

Napoleon on St. Helena.

Joan of Arc’s Death at the Stake,

Hermann Stilke, 1843.That makes the French edgy, defiant and vainglorious concerning their language. In Brussels, Jacques Delors, an 89 year old French economist and politician, the eighth President of the former European Commission and the first person to serve three terms in that office spoke very little English and used to hold all the official EU press conferences in French.During his service, he refused even to allow a simultaneous translation into English. This annoyed the non-French journalists, for most of whom English was the second language.A Danish correspondent once asked him why he was so insistent on French alone. „Because, Madame,“ he said sharply, „French is the language of diplomacy.“ And he added in a stage of whisper“….et de la civilisation“ ─ and of civilization too.

Although there is a channel that connects the two countries, it is more than obvious that they continue to dislike one another with the British grumbling that everything wrong with the European Union is the fault of the French, from the Common Agricultural Policy onwards.

If one adds the Balkan states that have recently become members of the EU or plan to enter the Union soon, the people in the EU form a mosaic of nations with completely different idiosyncrasies, customs, traditions, beliefs and culture (not to mention some ethnic misconceptions). With the Albanian nationalists thinking that they are purely descended from the ancient Illyrians and the people of FYROM claiming that they are the direct descendants of Alexander the Great, things might get even worse when these two countries enter the EU.

People from FYROM

comically pretending

to be ancient Macedonians.

So, no matter how hard somebody tries to “unity” those peoples under the same cultural and economic policy umbrella, it won’t work and in case it does, it won’t be for very long especially if high caliber and inspired European visionaries like Francois Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl are no longer around since every European nation has a few “Lord Palmerstons” of its own distrusting the rest of the EU countries as dishonest, deceitful, lascivious and mendacious.

A Germanized Europe

Although the German government says that its own success and its neighbors’ failures are unrelated, Dr. Pavlos Eleftheriadis, Associate Professor of Law and a Fellow of Mansfield College at Oxford University, believes that country has long enjoyed the economic zone’s policies at the expense of its weaker neighbors. He says that “Germany has for many years pursued a policy of wage suppression, which many economists have described as a competitive devaluation or ‘beggar thy neighbor’ policy. Germany’s gains in competitiveness were immediately translated to gains in trade, since the freedom of goods, services, persons and capital allowed German products to circulate freely and quickly throughout the European Union. These are the fundamental freedoms of EU law and are vigorously protected by the European Court of Justice. German policy would not have been successful without them.

Nationalist idealism

of a German state.

An 1848 painting entitled Germania.

Germany has also benefited from the fixed exchange rate that the Euro effectively secures between itself and its major European markets. This means that its export boom was not offset by a rise in its own currency. If Germany had been outside the Euro, currency appreciation would have hurt Germany’s gains. Not so in the Eurozone. While Germany has benefited so much from the Eurozone, its less successful partners are left to fend for themselves. The Eurozone lacks the automatic stabilizers that other currency unions apply among the various regions ─ namely, fiscal transfers such as unemployment and housing benefits, shared health care costs, or the pooling of bank risks and deposit insurance. The Eurozone also lacks the large movement of workers across state borders enjoyed by the United States, mostly due to language and regulatory barriers. These institutional features of the Eurozone have created a highly unfair economic union, which magnifies disproportionately the consequences of failure.”

Some might argue and say that all Eurozone members are subject to the same competitive environment and all are consented to its design by ratifying the relevant treaties. In other words, all member states had the chance to adjust.

Dr. Eleftheriadis proves that this argument is false: “Membership in the European Union has not improved the institutions of the weaker members. It has actually made them worse. When they joined the EU, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain opened their borders and exposed themselves to new waves of trade, immigration and finance. Competition with other member states was meant to bring about ‘creative destruction,’ whereby inefficient firms – i.e. those who could not compete internationally – would go out of business.

In order to avoid short-term hardships, the peripheral economies were set to receive large sums of EU funds by way of compensation. These funds were supposed to be invested in restructuring the domestic economies. But this happened very imperfectly.

The funds strengthened those who administered them. In the absence of a strong civil service in most of the peripheral EU members, these were simply the local political classes. In small societies with weak checks and balances, the effect was transformative. This money operated as a ‘natural resources curse’. Since the money was not the result of taxation, domestic accountability for its spending was seen to be an unnecessary luxury.

This situation was made worse once the Eurozone was created. With the ECB looking away, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Greece built not only asset bubbles with cheap and easy credit (which happened elsewhere) but also opaque and politically driven banking systems. As a result, cheap credit impeded reform and damaged institutions in all the countries of the periphery.

Membership in the Eurozone directed funds to wasteful investment, made cronyism exceptionally profitable, provided new incentives for political corruption and strengthened already existing hierarchies. If all the members of the Eurozone were equally strong, if they all had, for example, an outstanding and independent banking regulator, a powerful judiciary and strong internal mechanisms of accountability, perhaps these things would not have happened. Yet, they did happen.

The examples of the failed banks, Bankia in Spain, Allied Irish in Ireland, and Proton in Greece speak for themselves. In Greece, in particular, the EU has stood by while the political system has been undermined by a small group of oligarchs who have illegally occupied television frequencies for 25 years. By escaping any effective regulation and controlling news and commentary for their own purposes, they have dominated political and business life and undermined the credibility of the political class in its entirety. The bailout deal with the ECB, the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission has not touched their privileges.

In some of the members of the Eurozone the main legacy of the Euro is economic implosion, rising inequality and widespread corruption. This is not the result of isolated domestic failures. It is a result of collective European decision-making that misfired spectacularly throughout the periphery. The relentless pursuit of an ‘ever closer union’ made EU institutions neglect the question of the quality of this union. It is time to change course. Unless Europe addresses the deep unfairness at the heart of the Eurozone, the crisis is not going to end”.

Ulrich Beck, author of the book “German Europe” states: “The euro crisis is tearing Europe apart. But the heart of the matter is that, as the crisis unfolds, the basic rules of European democracy are being subverted or turned into their opposite, bypassing parliaments, governments and EU institutions. Multilateralism is turning into unilateralism, equality into hegemony, sovereignty into the dependency and recognition into disrespect for the dignity of other nations. Even France, which used to dominate European integration, must submit to Berlin’s strictures now that its international credit rating is threatened.

Ulrich Beck, author of the book “German Europe” states: “The euro crisis is tearing Europe apart. But the heart of the matter is that, as the crisis unfolds, the basic rules of European democracy are being subverted or turned into their opposite, bypassing parliaments, governments and EU institutions. Multilateralism is turning into unilateralism, equality into hegemony, sovereignty into the dependency and recognition into disrespect for the dignity of other nations. Even France, which used to dominate European integration, must submit to Berlin’s strictures now that its international credit rating is threatened.

How did this happen? The anticipation of the European catastrophe has already fundamentally changed the European landscape of power. It is giving birth to a political monster: a German Europe. Germany did not seek this leadership position – rather, it is a perfect illustration of the law of unintended consequences. The invention and implementation of the euro was the price demanded by France in order to pin Germany down to a European Monetary Union in the context of German unification. It was a quid pro quo for binding a united Germany into a more integrated Europe in which France would continue to play the leading role. But precise opposite has happened.

Economically, the euro turned out to be very good for Germany, and with the euro crisis Chancellor Angela Merkel became the informal Queen of Europe. The new grammar of power reflects the difference between creditor and debtor countries; it is not a military but an Economics logic. Its ideological foundation is ‘German euro nationalism’ – that is, an extended European version of the Deutschmark nationalism that underpinned German identity after the Second World War. In this way the German model of stability is being surreptitiously elevated into the guiding idea for Europe. The Europe we have now will not be able to survive in the risk–laden storms of the globalized world.

The EU has to be more than a grim marriage sustained by the fear of the chaos that would be caused by its breakdown. It has to be built on something more positive: a vision of rebuilding Europe bottom–up, creating a Europe of the citizen. There is no better way to reinvigorate Europe than through the coming together of ordinary Europeans acting on their own behalf”.

Germans are known for their race supremacy ideas no matter how hard they try to hide them. Although they have caused bloodshed and destruction all over Europe twice (WWI, WWII), they either suffer from memory lapses or they are completely incapable of learning from their past mistakes. A research concluded on March 8th 2013, clearly shows that Germany owes Greece 162 billion Euros in WWII reparations.

German troops

in front of buildings

set ablaze in Distomo,

during the massacre

Greece is the only country that hasn’t received the reparation money it deserves from the Germans. In the 80 page findings that include 109 archive files, experts found that Germany should pay Greece 108 billion Euros for damage to infrastructure and 54 billion Euros for a loan that the Nazi occupation forces obliged Greece to take in order to pay Berlin during the war. The reparations are equivalent to about 80 percent of Greek gross domestic product. Berlin has repeatedly claimed that all compensation claims were satisfied with the agreement of 1961. However, it comes out 1) that agreement referred to individual claims, not to state loan and 2) even this 1961-compensations were not fully paid. Instead, Germany tells Greece to forget all about the money that it owes.

“Forget the past and issues like the World War II reparations and look in the future”. That was the admonition of Gunther Krichbaum, chairman of European Affairs Committee at the German Federal Parliament, to a delegation of Greek lawmakers consisting of representatives of several political parties. When the Greeks brought on the agenda of the talks the issue of World War II reparations Kirchbaum’s comment was short and to the point, garnished with the noted German arrogance:“I would ask you to turn towards the future in a united Europe and the challenges we face.” “Germany’s position on the issue was clear and already known. That is that all reparations Germany had to pay to Greece for the damages and the atrocities during the WWII and the forced loan taken by the Nazis were settled through international and bilateral agreements”. Nothing has been settled, however as there are no international or bilateral agreements anywhere to be found!Germany, on the other hand, has been bailed out twice (if not three times) in its history. The ordinary German apparently has no historical knowledge about his country’s bail out history. He’s not aware that the failure to bail out Germany after WWI created the essential pre-condition for Nazism, and of course Germany was bailed out after world war II. The German economy was also bailed out when it was struggling after having absorbed East Germany.Attempts were made to „bail out“ Germany after WWI. There was the Dawes Plan in 1924 and the Young Plan in 1929, with both of them reducing the reparations amounts for Germany. However, there were a few things that eventually made the plans ineffective. The Dawes Plan had been put into effect after the Germans had deliberately destroyed the mark via hyper-inflation. That was done to spite the French, who had occupied the Ruhr because Germany had fallen behind in its reparation payments.

One-million mark notes

used as notepaper, October 1923.

The Young Plan went into effect in 1929 and was immediately crippled by the US Stock Exchange Crash in October 1929. An intrinsic part of the Young Plan consisted of loans to Germany, funded by bond purchases. It goes without saying that the market for such bonds, any bonds in fact, declined dramatically after 1929/30. So it wasn’t so much a failure to bail out Germany, as it was a reliance on loans to finance the reparations. Once the loans ceased, so did the reparations.So, it is somewhat irrational that Germany denies Greece and the rest of the southern countries some beneficial bail out policy choices out of its well known arrogant smugness. So, if one wonders why Angela Merkel is so much hated by the Greeks, the answer is that in Merkel’s face the Greeks not only see the German arrogance and the reflection of the German race supremacy but also the Nazi butchers who exterminated 1/3 of the country’s population in WWII.

The uniqueness of the Greek Crisis

Greece is a protectorate. It has always been after it was liberated from the Ottoman Empire. Europe’s superpowers had decided to speed up the death of the “sick old man” which was the Ottoman Empire. The European superpowers did not free Greece because they admire the Greek culture and heritage. They did it due to Greece’s geographic location which would help them in their geopolitical power play.

Greece went through a lot after its independence. Two world wars and a very bitter civil war whose impact still remain active in the infrastructure of the Greek society. So, not having the experience of a sovereign state with an organized public sector, Greece has always been the victim of political inequality. As Dr. Eleftheriadis puts it: “Greece’s accession to the European Union, in 1981, was supposed to improve things. EU membership, however, did not weaken traditional Greek hierarchies; it strengthened them. It was while the Greek economy was catching up to the rest of Europe ─ providing the oligarchs with new sources of credit and cash ─ that the country’s institutions began to break down.

Greece now ranks near the bottom of European countries when it comes to social mobility and near the top of rankings measuring inequality ─ a problem that Greek politicians and the media have almost entirely ignored. Even at the height of its spending before the crisis, Athens offered few benefits to the poor. Today, over 90 percent of the unemployed receive no government assistance whatsoever, some 20 percent of Greek children are estimated to live in extreme poverty, and millions of people lack health insurance. Moreover, after seven years of recession, none of the major political parties has proposed any serious reforms to the welfare state or to the health-care system in order to achieve universal coverage. They haven’t even expanded a pilot program to offer free lunches at public schools.

The Greek economy remains one of the least open in Europe and consequently one of the least competitive. It is also one of the most unequal. Greece has failed to address such problems because the country’s elites have a vested interest in keeping things as they are.

Since the early 1990s, a handful of wealthy families ─ an oligarchy in all but name ─ has dominated Greek politics. These elites have preserved their positions through control of the media and through old-fashioned favoritism, sharing the spoils of power with the country’s politicians.

Greek legislators, in turn, have held on to power by rewarding a small number of professional associations and public-sector unions that support the status quo. Even as European lenders have put the country’s finances under a microscope, this arrangement has held. The fundamental problem facing Greece is not economic growth but political inequality. To the benefit of a favored few, cumbersome regulations and dysfunctional institutions remain largely unchanged, even as the country’s infrastructure crumbles, poverty increases, and corruption persists. Greek society also faces new dangers. Overall unemployment stands at 27 percent, and youth unemployment exceeds 50 percent, providing an ideal recruiting ground for extremist groups on both the left and the right.

Meanwhile, the oligarchs are still profiting at the expense of the country ─ and the rest of Europe. Just as the oligarchs and their political allies use the media to avoid public scrutiny, so they rely on government regulations to retain control of the state. For the past three decades, two highly organized interest groups have profited the most under Greek law: first, elite professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, and engineers, and second, unionized employees of utilities owned wholly or partially by the state, such as the Public Power Corporation and the Hellenic Railways Organization.

The memberships of such groups are not large. Greece has only about 40,000 lawyers, 60,000 doctors, and 87,000 engineers. Public-sector employees number around 600,000. Yet what these groups lack in numbers they more than make up for in organization. By leveraging their ability to drive voter turnout in key urban constituencies, the professionals and the unions have won extraordinary privileges. For example, many professional associations can set standard prices for basic services, a form of collusion that is illegal in many economies but not in Greece. They are also permitted to self-regulate. When accusations of malpractice arise, the associations themselves have the exclusive right to discipline their members.

Moreover, special taxes fund their health-care and retirement accounts: since 1960, the pension fund for lawyers and judges has collected a stamp duty on all property transactions amounting to 1.3 percent of each sale price. And for decades, the doctors’ pension fund benefited from a 6.5 percent charge on the value of all drugs prescribed. Last year, Athens eliminated the charge at the troika’s request. But it has yet to dispense with any of the other taxes, which continue to redistribute millions of dollars from the poor to the wealthy”.

Common meal in Athens.

Unicef estimates that nearly 600,000 children now live under the poverty line in Greece. (The Guardian).

What Dr. Eleftheriadis doesn’t mention is that Greece continues to be ruled by the offsprings of those who collaborated with the Nazis in WWII. It may sound disgusting (it is) but it is true. The plutocratic elite in Greece mainly consist of the descendants of the German collaborators during WWII.

What Dr. Eleftheriadis doesn’t mention is that Greece continues to be ruled by the offsprings of those who collaborated with the Nazis in WWII. It may sound disgusting (it is) but it is true. The plutocratic elite in Greece mainly consist of the descendants of the German collaborators during WWII.

Has the average Greek working in the private sector received any benefits from the enormous amount of money that the EU has given Greece? The answer is no. All the money that Greece has received went to the plutocratic elite and the state mandarins who control the public sector. Instead of giving Greece any money, the EU, the ECB and the IMF should have demanded reforms that would cause the destruction of the oligarchy and the plutocratic elite. Instead, the money that Greece has received has been spent to strengthen the status quo of the oligarchs. Those who caused the crisis have increased their wealth and their privileges while the middle class is only a few steps away from vanishing into thin air. Europe has completely failed to address Greece’s inequality and humanitarian crisis.

A woman searching

for leftover groceries

at an open air market

(Neos Kosmos).

SYRIZA and Alexis Tsipras

SYRIZA’s states that its main goal is to terminate the modern Greek tragedy and the humanitarian crisis that the Greek people are going through. SYRIZA strongly insists on the abolishment of the memoranda that the previous Greek governments signed with the Troika of lenders. It plans on re-negotiating the loans. At the same time, it promotes a program of social and economic reconstruction, aiming at tackling the financial problems of the debt burdened citizens.

The new Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has announced that he will not unilaterally walk away from Greek obligations but instead, engage in a dialogue with creditor countries. He states that the issue of the inherited Greek debt stock needs to be re-addressed. The key point of Syriza is that a haircut of 50% would free up a large part of the country’s primary surplus and thus allow for some necessary spending to deal with the worst social problems besides promoting growth.

For creditor countries it is important to show to their citizens that they are not giving in to pressure to write down loans as this is a matter of principle. The solution to this argument is a moratorium on debt payments, a further adjustment of interest rates and maturities, and the linking of future repayments to reforms that promote economic growth. This would allow both sides to be satisfied. Germany and other creditors would not suffer a debt write-down while the Greek government would free up funds to spend on its policy priorities.

The second step is to kick start economic growth and pursue domestic reforms in Greece. Several of Syriza’s own policy priorities aim at generating growth which means that all of the domestic reforms shouldn’t be related to austerity. There is overwhelming evidence that austerity has been a disaster.

The new Greek finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, says that he aims at destroying the foundations of the Greek oligarchy. Tackling corruption and reforming the tax system, the civil service and other dysfunctional institutions will not be easy. But it is a vital necessity for Greece itself as well as a means of showing to creditor countries that the new government is serious about reforms.

The third step of a possible deal is creating the European environment in which this can work. It is obvious that if you want to deal with sluggish growth and large debt burdens, a deflationary economic environment is the last thing you want. The eurozone needs to get its inflation rate back to the 2% target as quickly as possible, which would help reduce the real value of debt. Prolonged and entrenched deflation does the opposite. Soon enough it would create additional problems not just for Greece, but also for other countries with a high debt-to-GDP ratio.

Supporters of Germany’s left-wing Die Linke party, hold placards as they show their support to Alexis Tsipras, leader of Syriza left-wing party after his speech to supporters in central Athens, late Sunday, Jan. 25, 2015. The placard, center, reads in German: ‚This is really a goodnight Mrs Merkel‘. (The Washington Post).

The European Central Bank has, eventually, done its part by starting quantitative easing. But as Mario Draghi, the ECB president, said, “QE alone will not be enough. We need a concerted investment push across the Eurozone that takes advantage of the new money and record low interest rates. If you don’t invest now, when would you ever do?” The European commission could also provide an extra boost for Greece and other crisis-stricken countries by making sure that the bulk of its announced investment program goes to where it is needed most.

If these steps are taken, Greece would be put back on to a growth path and when this is achieved, there is no reason why Greece could not service its debt once the moratorium runs out. It will be a significantly lower burden as the economy will have experience recovery by then.

According to the “Guardian”, the plan presented above would allow all parties to keep face. Germany and other creditor countries would not accept a haircut, but they would be flexible about repayment terms and about changing policy conditionality. The Syriza-led government, on the other hand, would be in a position to tackle Greece’s social and economic crisis, but would have to accept that its debt is not going to be written off. All eurozone countries, together with the European institutions, would make sure that they do not sink into a Japanese-style deflation. This is in everyone’s interest.Summing up, there is a way forward if everybody negotiates in good faith – but the stakes are very high. The danger of political accidents is clearly there. But a messy default and potential break-up of the currency union is in nobody’s interest. So in the end a compromise is the most likely outcome.If a beneficial agreement is finally reached, Greece will remain a happy protectorate under the umbrella of the West without having to fall into the arms of Putin.

Paul Krugman

In the five years (!) that have passed since the euro crisis began, clear thinking has been in notably short supply. But that fuzziness must now end. Recent events in Greece pose a fundamental challenge for Europe: Can it get past the myths and the moralizing, and deal with reality in a way that respects the Continent’s core values? If not, the whole European project — the attempt to build peace and democracy through shared prosperity — will suffer a terrible, perhaps mortal blow. First, about those myths: Many people seem to believe that the loans Athens has received since the crisis broke have been subsidizing Greek spending. The truth, however, is that the great bulk of the money lent to Greece has been used simply to pay interest and principal on debt.

In fact, for the past two years, more than all of the money going to Greece has been recycled in this way: the Greek government is taking in more revenue than it spends on things other than interest, and handing the extra funds over to its creditors. Or to oversimplify things a bit, you can think of European policy as involving a bailout, not of Greece, but of creditor-country banks, with the Greek government simply acting as the middleman — and with the Greek public, which has seen a catastrophic fall in living standards, required to make further sacrifices so that it, too, can contribute funds to that bailout.

One way to think about the demands of the newly elected Greek government is that it wants a reduction in the size of that contribution. Nobody is talking about Greece spending more than it takes in; all that might be on the table would be spending less on interest and more on things like health care and aid to the destitute. And doing so would have the side effectof greatly reducing Greece’s 25 percent rate of unemployment. But doesn’t Greece have an obligation to pay the debts its own government chose to run up? That’s where the moralizing comes in. It’s true that Greece (or more precisely the center-right government that ruled the nation from 2004-9) voluntarily borrowed vast sums.

It’s also true, however, that banks in Germany and elsewhere voluntarily lent Greece all that money. We would ordinarily expect both sides of that misjudgment to pay a price. But the private lenders have been largely bailed out (despite a “haircut” on their claims in 2012). Meanwhile, Greece is expected to keep on paying. Now, the truth is that nobody believes that Greece can fully repay. So why not recognize that reality and reduce the payments to a level that doesn’t impose endless suffering? Is the goal to make Greece an example for other borrowers? If so, how is that consistent with the values of what is supposed to be an association of sovereign, democratic nations?

The question of values becomes even starker once we consider why Greece’s creditors still have power. If it were just a matter of government finance, Greece could simply declare bankruptcy; it would be cut off from new loans, but it would also stop paying off existing debts, and its cash flow would actually improve. The problem for Greece, however, is the fragility of its banks, which currently (like banks throughout the euro area) have access to credit from the European Central Bank. Cut off that credit, and the Greek banking system would probably melt down amid huge bank runs. As long as it stays on the euro, then, Greece needs the good will of the central bank, which may, in turn, depend on the attitude of Germany and other creditor nations. But think about how that plays into debt negotiations. Is Germany really prepared, in effect, to say to a fellow European democracy, “Pay up or we’ll destroy your banking system?” And think about what happens if the new Greek government — which was, after all, elected on a promise to end austerity — refuses to give in? That way, all too easily, lies a forced exit of Greece from the euro, with potentially disastrous economic and political consequences for Europe as a whole.

Objectively, resolving this situation shouldn’t be hard. Although nobody knows it, Greece has actually made great progress in regaining competitiveness; wages and costs have fallen dramatically, so that, at this point, austerity is the main thing holding the economy back. So what’s needed is simple: Let Greece run smaller but still positive surpluses, which would relieve Greek suffering, and let the new government claim success, defusing the anti-democratic forces waiting in the wings. Meanwhile, the cost to creditor-nation taxpayers ─ who were never going to get the full value of the debt ─ would be minimal. Doing the right thing would, however, require that other Europeans, Germans in particular, abandon self-serving myths and stop substituting moralizing for analysis.

Can they do it? We’ll soon see.

That doesn’t mean however that the Eurozone won’t be a thing of the past. Sooner or later, the cultural and ethnic differences among the several European nations as well as the financial interests of Germany will lead to the collapse of the Eurozone. Let’s all hope that this collapse isn’t accompanied by WWIII.